At the hotel bar, they tell me Johnny Knoxville just left. They say he’s too old to do stunts anymore, but he’s a nice guy.

I’m staying at the Hollywood Roosevelt, which I find out later is historic for several reasons: Shirley Temple did her iconic stair dance here, it was the home of the first Academy Awards, movie upon movie has been filmed here. It’s also haunted by either the ghost of Marilyn Monroe or a child in a blue dress named Caroline, which is a pretty wide net to cast in terms of ghosts. But the lights in my hotel room do flicker and randomly turn on, waking me from a deep sleep in the middle of the night.

Two of my friends come to visit me at the hotel for drinks by the pool. One of the friends is incredible with a pure heart. The other says something so offensive to me that I tell him I will never speak to him again. When I finally crawl into bed, I sleep for 13 hours straight, all of Hollywood still going outside my window, all of that grime and glitz, all of those people out there wanting more of everything, all the time.

Bjork at The Shrine

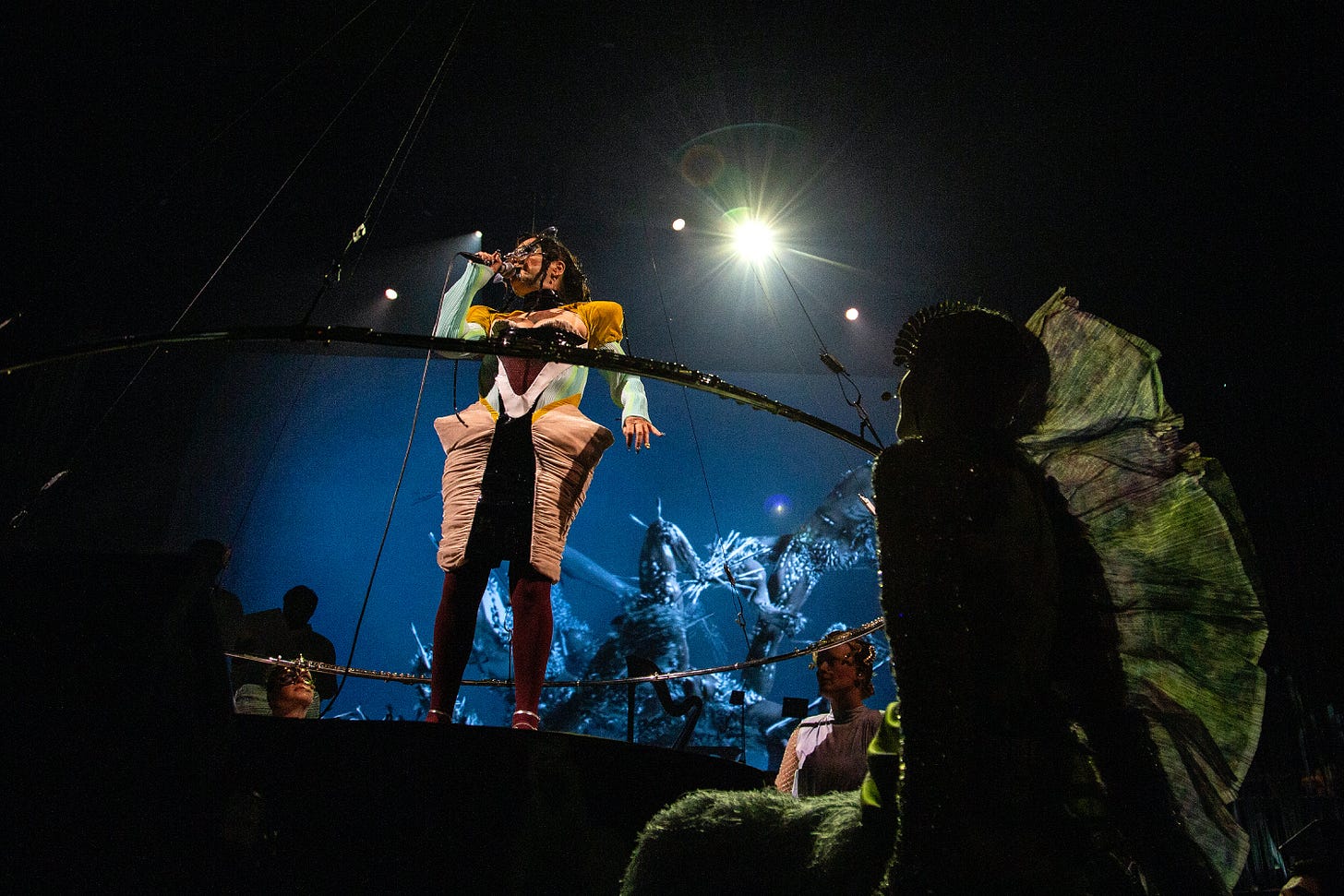

On the stage of the ornate Shrine Auditorium, long white strings hang from the ceiling down to the floor. Beautiful flowers and birds are projected onto the strands, turning them into a screen.

Bjork requests that you take no photos, hums a kind voice over the din of the crowd. Photos are distracting to Bjork. Please stay in the moment. We will post photos after the show.

It seems pretentious, but apparently a man got knocked out for taking pictures at last night’s show, or at least that’s the rumor making its way through the crowd. So we keep our phones down.

Then the lights go down, and a small choir all dressed in white files onto the stage. They sing a beautiful, sad song, and their voices are so gorgeous that it takes me a minute to realize they are singing accusations at the crowd, blaming all of us for climate change.

The chorus files off and the string screen shifts. Suddenly, a gigantic fluorescent Bjork flashes onto the screen, singing and gyrating and melting before our eyes in magenta and yellow. Then, finally, we can hear her, singing along with the image of herself as it shimmers before us.

The crowd starts to shout, but we still can’t see her. From beyond the curtain, in the darkness, she begins to sing I care for you, I care for you, I care for you and the curtains part just slightly. The crowd goes wild again, but still she isn’t visible.

As she sings Care for me, care for me, care for me, vulnerably, as if asking us to be careful with her, as if asking permission to come out, the curtain ever so slowly splits, until finally there she is, the crowd thundering, her voice still quivering Care for me, care for me, care for me.

The Cornucopia shows are Bjork’s most ambitious yet. Billed as a sci-fi theater production based on her Utopia album, the art surrounding the performance is concerned largely with the environment: think swirling projections that vaguely resemble plants blooming open behind her. The costumes are by Balmain, the choreography is bananas, the aesthetic is singularly Bjork. In the middle of the show, the white screen returns and a projection of Greta Thunberg’s climate change manifesto slowly scrolls past.

For the first few songs, what struck me most — beyond the absolutely insane amount of money it must have cost to make all of this happen — was the sense that Bjork was hiding. Between her slow emergence from behind the curtain to the silver mask which reflected all of the spotlights so you couldn’t get a clear glimpse of her face to the white sound booth in the back of the stage which she kept returning to in order to sing while obscured, I couldn’t help but get the feeling she wanted to physically hide herself so the work itself took center stage.

The rest of the show might as well be an acid trip in the sense that any description I can offer would be like recounting a dream that moved me deeply. The lights, the projections, the dozen flute players, the exquisitely timed show running like the theater production of a mad woman with a pristine vision. I’ll spare the rest of the spoilers, but at one point I whispered to myself “Is that man playing water like an instrument?” and he was. At every turn, the show was like nothing I have ever seen before.

Pipilotti Rist: Big Heartedness, Be My Neighbor

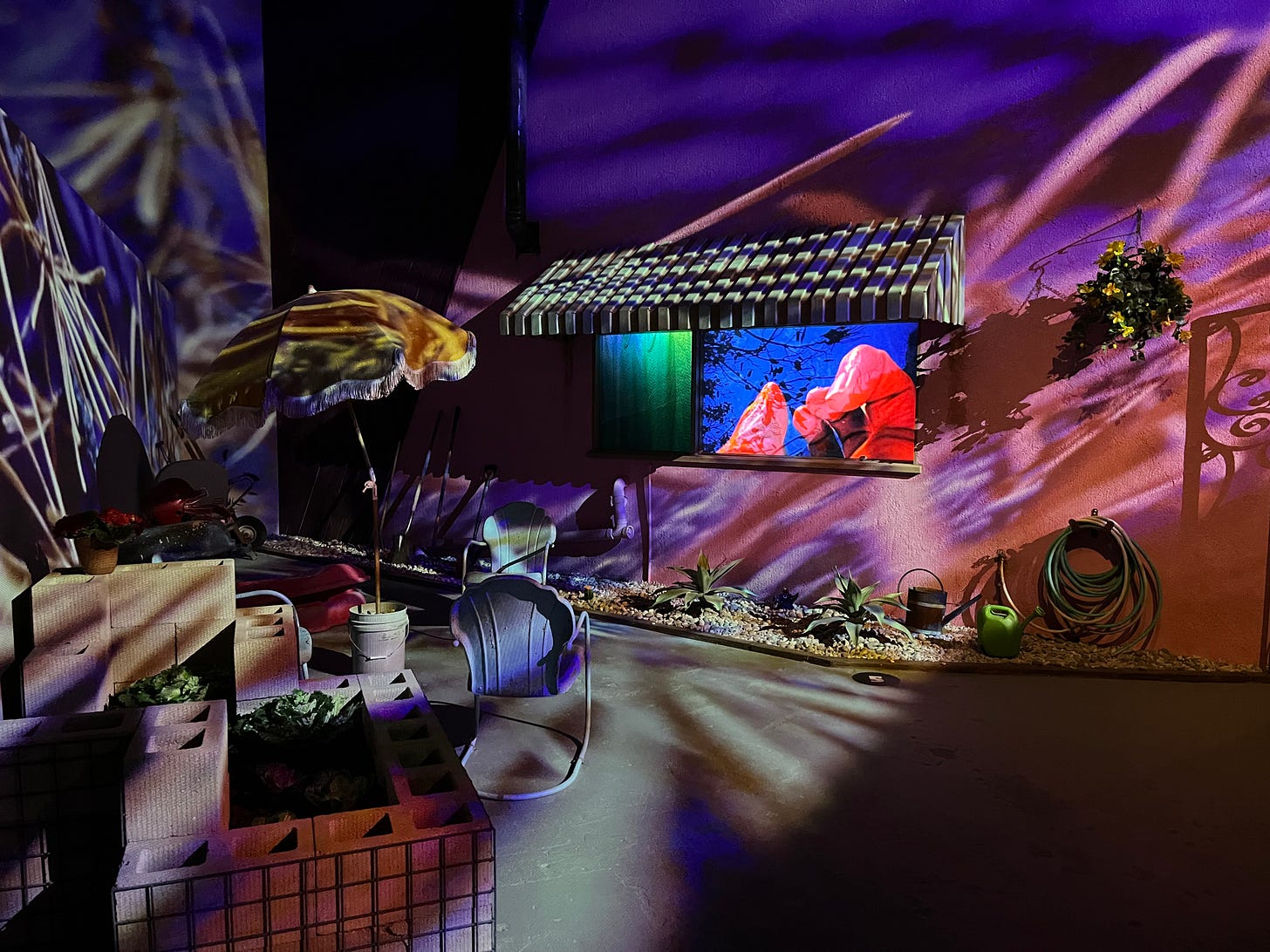

The Geffen Contemporary at the MOCA is one of my favorite places in Los Angeles to see art because it’s right in line with east coast staples like Dia:Beacon and MASSMoca. A former police car warehouse, the Geffen gives enough space to artists to allow them to go big, immersive, spectacular. And that’s exactly what Pipilotti Rist, a Swiss visual artist, has done with her first west coast retrospective, “Big Heartedness, Be My Neighbor.”

One of the most troubling trends I’ve noticed in art lately are the “Immersive Art Warehouses” that have been popping up in cities across America. From “immersive” Van Gogh to companies like Seismique, these initiatives are billed as making art more accessible to the masses. The problem is that the designs for most of these rooms are rip-offs of actual art by real artists.

Yayoi Kusama’s “Infinity Rooms,” and Rist’s light strands are two examples of direct rip-offs that eat me up a little.

Both of these artists worked for their entire lives to break into the art world, only to have their concepts watered down and diluted.

But back to the show. I stumbled on Rist’s first show at the New Museum by mistake a few years ago in New York. I don’t love video art, but Rist is doing something elevated with the form. Her video work explodes across walls, or inhabits miniature screens nestled in mirrors. She’s either completely immersing you in the imagery or pulling you in close to make you find it.

At the Geffen, stepping into Rist’s world is like stepping into an underwater backyard. A full-scale home with a back yard sets the scene, but Rist’s gigantic projections of coral, grass, water droplets, and hands juxtaposed against tree branches, make the space watery and electric.

Stepping into Rist’s signature light strands as they shifted color in tune to a perfectly selected soundtrack, I suddenly found myself weeping. It struck me that beyond the orchestration of the color shifting, Rist had also been so intentional about the music in order to create an emotional moment. That’s the part of the work that no immersive art exhibit can capture. It’s purely her.

Beyond the underwater backyard, the exhibit also housed a psychedelic library and living room, along with a few rooms of Rist’s more traditional video work. In each area, the artist provides beanbags to lay on while her projections flicker on gigantic walls. In the living room, you can crawl onto a white bed and have a projection of outer space swirl over your body, or lay on the floor and watch a gigantic video of a women who has her period swimming in red water cutting to fields of red tulips cutting to fingers clawing through dirt.

In one of the most effective rooms, twin walls flicker with videos of jellyfish floating above records on the ocean floor and images of roses hovering in stormy skies. The videos alone are beautiful, but again, the music pushes everything forward: the soundtrack is a woman singing an acoustic version of Chris Isaak’s “Wicked Game,” which seems innocent enough until another woman appears on the track, shrieking the words alongside the singer until she reaches a fevered, psychotic pitch, maniacally screaming NO, I DON’T WANNA FALL IN LOVE with such desperation that I had to leave the room.

One of the final rooms features one of Rist’s most famous works, “Ever Is Over All (1997),” which is one of the pieces that launched her career and served as the main inspiration for Beyonce’s “Hold Up” video.

In “Ever,” a woman ambles through the streets in glittering ruby slippers, holding what appears to be a flower. Skipping and laughing, she smashes in car windows until police sirens begin in the distance.

Eventually, a police officer begins to trail her — and for a moment, you think she might get caught. But it turns out the police officer is a white woman, who simply smiles at Rist encouragingly. The video is incredible, but the ending doesn’t hold up — it’s impossible to view it now without asking questions about the implication of a white woman casually walking down the street and smashing things while another white woman lets her get away with it.

But overall, Rist continues to deliver what other art companies will always attempt to rip off: Immersive moments that often feel like stepping into a pool of feelings. She wants your emotions to bubble to the surface, and the scenes she orchestrates make it almost impossible to stand in her work and not feel something.

The Museum of Jurassic Technology, or: Spoilers Ahead

70% of my ex-boyfriends have told me that I need to visit the Museum of Jurassic Technology, and 100% of those ex-boyfriends have asked me not to do any research about the place before I went. So for years, I’ve resisted the urge to Google it or do any research. I’ve kept the urge locked in a box in my chest.

So when it was finally time to see the place with a group of my friends, I had no idea what to expect. And it took me some time, after stumbling through the first few exhibits, to wrap my head around it.

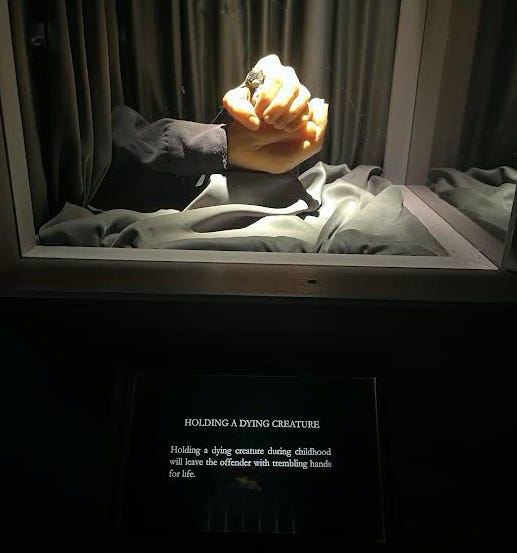

The best way I can describe it is as a Surrealist Museum of Natural History. While the exhibits themselves are elaborate and replicate the traditional museum experience, they are all based on false histories.

In one room, every recorded Trailer Disaster is noted as a pinprick of light on a lit map of the world. Below the map, intricate dioramas of trailers in the desert at night replicate the history as if it’s as real as the Titanic sinking.

In another room, scientific microscopes invite you to lean in to see what’s contained in the petri dishes — only for you to discover that each dish is an assemblage of small glittering gems shaped into mosaics of bouquets, roosters, and elaborate patterns.

In one of my favorite rooms - and the only one I was brave enough to sneak a picture of - were exhibits of fake wives’ tales that were both mesmerizing and haunting.

Every single one was short-story fodder.

Beyond the insane amount of exhibits, the rooftop of the Jurassic Museum of Technology turns out to be an oasis. There, surrounded by lush plants and concrete arches, you’re served tea in a garden full of beautiful doves.

Like the Bjork show, no phones are allowed. And like the Bjork show and the Rist installation, the experience is so beautiful that you probably wouldn’t want to use your phone anyway.

Very excited to read more newsletters from you, Sarah!